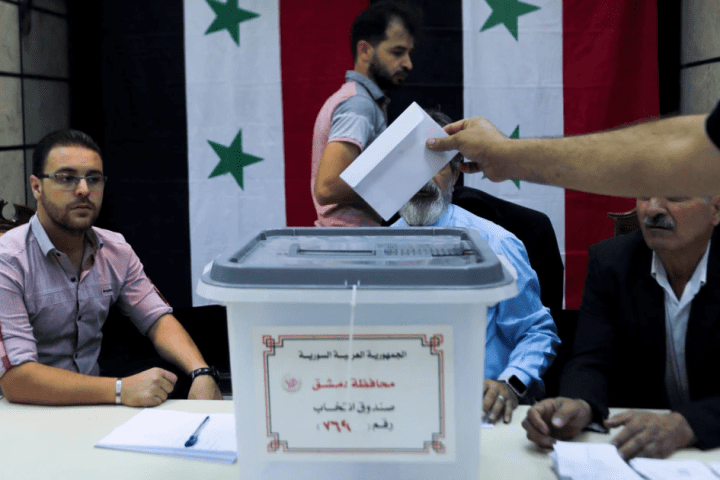

Syria held its first parliamentary elections since the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad. The new authorities, led by President Ahmed al-Sharaa, call the vote a step toward a “return to normal life” after nearly 14 years of civil war.

However, critics claim the process was opaque, manipulated, and bore little resemblance to democracy.

The First Elections of the New Syria: Limited, Indirect, and Far from Democratic

Citizens did not participate directly in the vote. Under provisional rules, a third of parliament (70 of 210 seats) is personally appointed by al-Sharaa, while the remaining members are selected through committees also formed by the government.

About 7,000 electors from 60 constituencies were eligible to vote; they were selected by special commissions appointed by the authorities. Observers believe this system leaves room for manipulation and exceptions.

Nawar Najma, a spokesperson for the Supreme Electoral Committee, stated that the main requirement for candidates was “a complete renunciation—in both words and deeds—of the former Assad regime.”

According to the organizing committee, more than 1,500 candidates participated in the elections, all as independents, as all political parties had been dissolved and a new registration system had not been established.

According to the interim constitution adopted in March, the new parliament will exercise legislative functions until a permanent constitution is approved and general elections are held.

Lack of Transparency and Exclusion of Regions

Haid Haid, an expert at the Chatham House think tank and the Arab Reform Initiative, told the Associated Press that the elections “were conducted without transparency at all stages.”

“This is especially true for the formation of subcommittees and electoral colleges—there is no oversight, and the process is vulnerable to manipulation,” he noted.

He also claimed that electoral authorities excluded names from lists without explanation.

Critics argue that the current system favors influential figures and effectively maintains power in the hands of the country’s current leaders, rather than leading to genuine reform.

More than a dozen non-governmental organizations stated in a joint statement that the current model allows al-Sharaa “to form a parliamentary majority from individuals he personally selected or loyal to him,” which, they say, “undermines the very principle of political pluralism.”

“Call it anything you want, but it’s not an election,” Bassam Alahmad, director of the French organization Syrians for Truth and Justice, told AFP.

Excluded Territories and Representation

The authorities explain their refusal to hold direct elections by arguing that holding a universal suffrage is impossible after 13 years of war, which has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and left millions of Syrians undocumented or outside the country.

The election process did not include the predominantly Druze province of As-Suwayda, which has seen armed clashes involving government forces in recent months.

The Kurdish northeast, which, according to al-Sharaa, “remains outside Damascus’s control,” also did not participate in the elections.

Thus, the Kurdish and Druze minorities are effectively deprived of representation, and their 32 parliamentary seats will remain vacant.

Furthermore, low participation by women was noted—they constituted only 14% of the candidates.

The head of the Supreme Electoral Committee, Mohammad Taha al-Ahmad, told the DPA news agency that the president would review the results “to ensure fair representation of women and minorities.”

He stated that al-Sharaa intends to use his authority to appoint 70 MPs to increase the proportion of women to 20% and balance the composition of parliament.

Authorities declare the beginning of a new phase

Speaking at the National Library in Damascus, Ahmed al-Sharaa called the elections proof that Syria “has been able to launch a political process in just a few months that is consistent with current conditions.”

“We must pass numerous laws to move forward on the path to recovery and prosperity. Building Syria is a shared mission, and every Syrian must contribute,” he declared.